Don't Forget to Share!

-Video is at the bottom of the page-

I. Corinth: The City and Its History

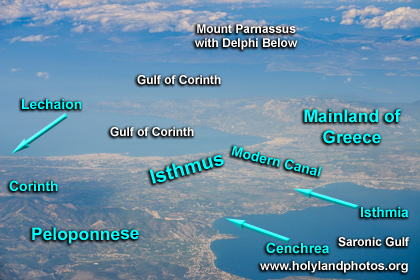

The ancient city of Corinth lay just a short distance south of the narrow isthmus that joins the Peloponnesus to the central part of Greece. Its location thus enabled it to achieve an importance in ancient Greece that few other cities could have rivaled. Anyone traveling from Macedonia, Attica, or Athens to Arcadia, Argos, Achaia, or Sparta, would have had to travel across the isthmus of 5,950 meters and pass Corinth en route. Its strategic location also enabled it to dominate two important harbors, one on each side of the isthmus. Eight and a half kilometers to the east was Cenchreae (Kenchreai) on the Saronic Gulf, which gave access to ships traveling from Asia and the Aegean Sea (Apuleius, Metamorphoses 10.35); and two kilometers to the north was Lechaeum (Lechaion) on the Gulf of Corinth, which gave access to the Adriatic Sea and Italy. This ideal situation of Corinth was noted by the ancient geographer Strabo (Geogr. 8.6.20) and was known to Latin writers, who spoke of bimaris Corinthus, “Corinth on two seas” (Horace, Carm. 1.7.2; Ovid, Heroides 12.27). Consequently, after classical Athens, Corinth was the second most important city in ancient Greece, but in the first century a.d. it would have been more important than Athens. Along with Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch on the Orontes (Syria), it would have been one of the four most important cities of the Mediterranean world.

Many springs in the area and the nearby rivers, Nemea and Longopotamus, made the coastal area about Corinth quite fertile and rich. The city of Corinth was built to the north of the base of a peak called Acrocorinth, which was 575 meters high, and from at least the fourth century b.c. it served as the citadel of Corinth. On the summit of Acrocorinth was a Temple of Aphrodite Hoplismene (with a statue of her bearing arms), the patroness of Corinth. Behind the temple was a spring, apparently fed by the same water as the Peirene fountain in the agora (forum) of Corinth (Pausanias, Descr. Graec. 2.3).

Both Acrocorinth and the city were enclosed within a walled area, more or less trapezoidal in shape, which was over four square kilometers in area. The circumference of the walls was over 10,000 meters. Two other parallel walls connected the enclosed city with the port of Lechaeum. Not all of that enclosed area was built up and populated, so there was considerable open space for parks and springs. Corinthia, the territory controled by the city-state, stretched well beyond the narrow isthmus and included to the north the promontory along the Halcyon Bay and to the south the area roughly up to Mount Onium.

The area of Corinthia had been settled already in Neolithic times, and early Helladic settlements were extensive there. The origins of the city of Corinth, however, are shrouded in legends. Apparently it was called at one time Ephyrē, and Sisyphus, son of Aeolus, whom Homer called “the most crafty of men” (Iliad 6.152–54), was said to be the king of Ephyrē.

The historical period of Corinth is divided into two eras. The earlier era begins with the Dorian invasion of the Peloponnesus in the tenth century b.c., when Temenos, one of the Heraclidae, conquered Argos. Around 850 b.c., the Dorian oligarchy of the Bacchiadae ruled in Corinth, named after Bacchis, king of Corinth. In this early period, about 733, the city spread its influence by establishing colonies at Corcyra (modern Korfu), off the coast of Epirus, at Syracuse in Sicily, and elsewhere. About 725, a renowned style of Greek pottery was developed that came to be known as Proto-Corinthian and Corinthian ware, which was widely used in the eastern Mediterranean world. Corinth was famous also for a fleet of triremes, which the historian Thucydides later praised (Hist. 1.13.2–4). Homer sang of “wealthy Corinth” (Iliad 2.570), and that was echoed by Strabo centuries later (Geogr. 8.6.20).

About 657, Cypselus overthrew the Bacchiadian oligarchy and set himself up as tyrannos of Corinth, under whom the city again thrived in prosperity, power, and colonization. Cypselus reigned until 625, when he was succeeded by his son Periander (625–585), who continued his father’s policies. In the sixth century, Periander built the diolkos across the isthmus at its narrowest point, i.e., from Schoenus on the Saronic Gulf, not far from Cenchreae, to the opposite bank, a distance of 5950 meters (Strabo, Geogr. 8.2.1; 8.6.22). Diolkos means “hauling across,” and it was the name given to a stone-paved road with channels constructed in it, which guided the wheels of a movable platform used to transfer small boats and their cargo across the isthmus from one gulf to the other. This was intended to be a shortcut for shipping freight from Asia to Italy, which would spare small craft from coping with the wind-swept and dangerous route around Cape Maleae and the other capes at the southern tip of the Peloponnesus. (The diolkos was a substitute for a canal, which many administrators of Corinth and elsewhere had hoped to construct throughout the centuries, e.g., Demetrius I Poliorcetes of Macedon [end of the fourth century b.c.]; Julius Caesar, Caligula, and Nero [in the first century b.c. and a.d.]. Only in 1881–93 was the Corinthian Canal finally cut through the isthmus by French engineers to connect the two gulfs.)

When Periander died, the rule passed to his nephew Psammetichus (Cypselus II), who was assassinated within a short time. Then a constitutional government was set up with eight probouloi (executive magistrates) and a council of 80 men to rule instead. In the early sixth century, the Isthmian Games were started, and they continued to be sponsored by the city of Corinth for centuries. In the sixth and fifth centuries, Corinth often sided with other Peloponnesian city-states and battled against other cities throughout Greece, especially Sparta, Athens, and Thebes. In the fifth century, in particular, it countered the influence of Athens, which sought to spread its dominion over Megara and other towns about the Corinthian Gulf. This led eventually to the Peloponnesian War (431–404 b.c.). Corinth suffered greatly during the war, but in the end the Athenian fleet was defeated at Aegospotami in the Hellespont, after which Athens capitulated (404). Eventually, in 395 Corinth joined forces with Argos, Athens, and Boeotia to curb the spread of Sparta’s domination, which led to the so-called Corinthian War. As a result of the war Corinth lost its independence and was united with Argos (395–386).

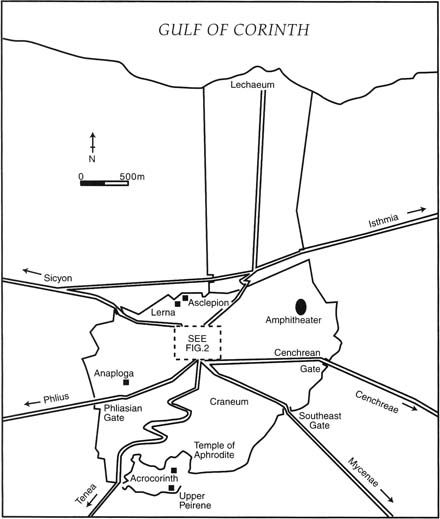

Figure 1. City plan of Corinth (Redrawn from Murphy-O’Connor 1983a: 20, fig. 4.)

By this time the influence of Macedonia in northern Greece was spreading, and in 338 the battle of Chaeronea took place, when Philip II of Macedon conquered the Greek city-states and strove to unite Greece into one kingdom. That was also the beginning of the Hellenic League, which was proclaimed at Corinth by Philip, as he started his crusade against Persian interference in the land. In 280, the Achaean League was refounded, and it lasted until 146. In 243, a leading statesman of the League was Aratus of Sicyon, a neighboring city-state; he freed Acrocorinth and Corinth from Macedonian domination and its degrading influence; he adopted an explicit anti-Macedonian policy, which Corinth eventually also espoused.

Roman contact with Greek city-states began about 228 b.c., and Roman interference in the Peloponnesus became strong in 197, after the Second Macedonian War (200–197), when Roman officials sought to reorganize boundaries and alter civic governments. A few years later Corinth became the chief city-state of the Achaean League, which was then seeking to offset Roman interference. In 147, a Roman delegation arrived in Corinth, demanding the dissolution of the League. The result was the Achaean War. Then under the leadership of the Roman general, Lucius Mummius, Corinth was defeated in battle in 146; the city was sacked, burned, and razed to the ground. All the male citizens were killed, and the women and children sold into slavery (Pausanias, Descr. Graec. 1.20.4; Cicero, Verr. 2.55). “The Sicyonians obtained most of the Corinthian territory” (Strabo, Geogr. 8.6.23). Mummius, however, shipped most of the art treasures of Corinth to Rome (Cicero, De Officiis 3.11.46; Vitruvius, De archit. 5.5.8), and he was awarded the title “Achaicus,” so that he is known in history as Lucius Mummius Achaicus (Pliny, Nat. Hist. 35.8.24; Arafat, Pausanias’ Greece, 89–97). City-states such as Corinth, Euboea, Phokis, came under Roman domination, rule, and taxation. So ended the early era of Corinth.

Ancient writers report that for more than a century the site of Corinth was desolate and largely deserted. The chōra, or site where the city had been, became ager publicus (Roman public property). Sometime between 79–77 b.c., the future Roman orator and statesman, M. Tullius Cicero (106–43), while still a student in Greece, visited the site of Corinth and wrote of it: Corinthi vestigium vix relictum est, “hardly a trace of Corinth has been left” (De lege agraria 2.32 §87 [composed in 63]). Among Cicero’s letters there is also one sent to him by S. Sulpicius Rufus, who speaks of Piraeus and Corinth as towns once most florishing, but now lying prostrate and demolished before one’s very eyes (oppida quodam tempore florentissima, nunc prostrata et diruta ante oculos iacent [Ad Fam. 4.5.4]). See also Velleius Paterculus, Hist. Romae 1.13.1. However, elsewhere Cicero admits that as a youth he was in Peloponnesus and saw “Corinthians” living there, as he had seen Argives and Sicyonians (Tusc. Disp. 3.22.53 [composed in 45 b.c.]). For some natives continued to dwell in Corinth as squatters, as material archaeological evidence shows. Williams (“Corinth 1977,” 21) reports: “Some evidence has been accumulating over the years of excavation, however, that reinforces the statement made by Cicero that persons did live among the ruins of the city in the interim period.” He mentions stamped amphoras, coins from before the Roman refounding of Corinth, continuity of cult places, pottery, and glassware. So it appears that the destruction of ancient Corinth may have been far less extensive than is normally thought. Similarly, Wiseman reports, “The destruction of Corinth was far less extensive than scholars have preferred to believe.… At the South Stoa the monuments along the terrace were carried away, but the buiding itself was standing ‘fairly intact’ when the colony was established in 44 b.c.” (“Corinth and Rome I,” 494). See further Broneer, South Stoa, 100–155; Oster, “Use, Misuse,” 54–55.

At any rate, the second era of ancient Corinth began in 44 b.c., when Julius Caesar, a short time before he was assassinated, issued a decree refounding Corinth as a Roman colony, Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis, “Corinthian Colony, to the honor of Julius” (Dio Cassius, Rom. Hist. 43.50.3–5; cf. Pausanias, Descr, Graec. 2.1.2; 3.11.4; Broneer, “Colonia”). This second period is usually called Roman Corinth, which differed considerably from the older Greek city and its glorious past. As a Roman colony, its culture and laws were those of Rome; the Roman town was laid out in a grid of parallel streets according to Roman town-planning, with fine public buildings. The new town’s forum was built about three feet higher than the old Greek agora and was expanded to the south. Some edifices of the pre-146 Corinth were rebuilt. The south stoa of the old city was reused, as was the archaic temple (of Apollo?), but they were rebuilt in italic architectural style. Temple E (see fig. 2, no. 19), dedicated to the imperial cult, at the west end of the forum, was built totally in Roman design and dominated the forum.

Some of the intrigues of J. Caesar, Brutus, Octavian, and M. Antony ensued on Grecian territory, especially the battle of Actium (31 b.c.) off the coast of Epirus. In time, Roman Corinth became the capital of the province of Achaia and the seat of the Roman governor, the center for assizes and the collection of taxes. Under Augustus, about 27 b.c., Achaia (roughly the equivalent of modern Greece, save for Thessaly, Macedonia, and Crete) was made a senatorial province. The strategic location of the capital, with Acrocorinth as a point of defense, and its character of a crossroad between East and West made it necessary for the Roman occupiers to rebuild the city. This they did, stressing discontinuity with the past (old Greek Corinth). Romanitas and a prolonged pax Romana reigned until Byzantine times.

About 7 b.c., Roman Corinth recovered the administration of the Isthmian Games, which ranked in importance just after the Olympics; they were held every other year. To these were added the Caesarean Games and the Imperial Contests, which were held every four years in honor of the emperor Tiberius. Because of later administrative difficulties, Tiberius attached Achaia to the imperial province of Moesia (a.d. 15 [Tacitus, Ann. 1.76]), but eventually, in a.d. 44, the emperor Claudius restored Achaia to the full status of a senatorial province. So Corinth continued to be the seat of the proconsul governing the Roman province of Achaia in the time when Paul first visited and evangelized the city.

After Paul’s time, noteworthy events in Corinth included the fifteen-month visit of Nero to Greece in the years 66–67, when he granted the province of Achaia autonomy, libertas, and immunitas (which proved to be shortlived [Pausanias, Descr, Graec. 7.17.3–4]) and started the building of a canal across the isthmus, where the diolkos had been; but that project did not continue long. In the year 77, an earthquake struck the area and destroyed much of Roman Corinth, which was subsequently rebuilt. Under the Flavian emperors, the Latin name of the colony was sometimes given as Colonia Iulia Flavia Augusta Corinthiensis, “Julian, Flavian, Augustan, Corinthian Colony.” So it appears at times on coins of the Flavian period, especially in the 80s. The earthquake and the rebuilding of Corinth must be kept in mind when one reads Pausanias’s description of the Corinth that he knew. In the second century, Corinth retained its importance, as is evident from a remark of Apuleius (a.d. 123–?), calling it caput totius Achaiae provinciae, “head of the entire province of Achaia” (Metamorphoses 10.18).

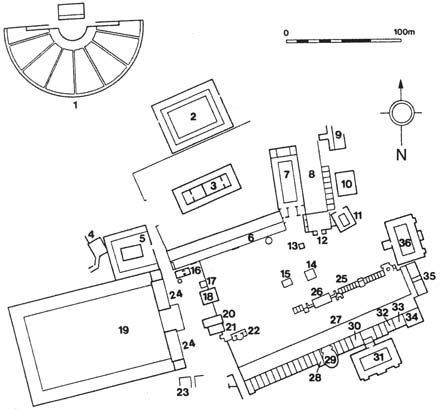

Figure 2. Plan of Corinth—central area, ca. 50 c.e. 1, theater; 2, N market; 3, archaic temple, 6th century b.c.; 4, Fountain of Glauke, 6th century b.c.; 5, temple C (unidentified); 6, NW stoa; 7, N basilica; 8, Lechaeum Road; 9, bath (of Eurycles?); 10, Peribolos of Apollo; 11, Fountain of Peirene; 12, Propylaea; 13, Tripod; 14, statue of Athena; 15, altar (unidentified); 16, temple D (Tychē); 17, Babbius monument; 18, Fountain of Poseidon (Neptune); 19, temple of the imperial cult; 20, temple G (Pantheon?); 21, temple F (Aphrodite); 22, unidentified building (temple or civic structure); 23, “Cellar Building” (public restaurant or tavern); 24, W shops; 25, central shops; 26, bēma; 27, S stoa; 28, room XX (Sarapis shrine); 29, Bouleutērion; 30, “Fountain House”; 31, S basilica; 32, room C (Agonotheteion); 33, room B; 34, room A; 35, SE building (Tabularium and library?); 36, Julian Basilica. (Redrawn from Furnish, II Corinthians AB, 11, fig 2.)

Much can be learned about the shape of Roman Corinth, because details of its history and geography have been recorded by Strabo (64 b.c–a.d. 21) in his Geographia 1.3.11; 10.5.4.; 17.3.25; and esp. 8.6.20–23; and also by second-century Pausanias (fl. ca. a.d. 150) in his Descriptio Graeciae 2.1.1–2.5.5 (also 5.1.2; 7.16.7–10). Strabo visited Roman Corinth in 29 b.c. and completed his geographical work about 7 b.c., but revised it about a.d. 18, a few years before his death. Hence much of what Strabo records about ancient Corinth would be true of the Roman city that Paul knew. Pausanias, however, seems to have visited rebuilt Corinth sometime after a.d. 165; consequently, his elaborate description of Corinth sometimes includes things that would not have been seen when the apostle Paul was there. Yet his account, when read with care and in comparison with Strabo, is still valuable for our knowledge of first-century Corinth.

The texts of Strabo and Pausanias, along with many details about Roman Corinth found in other ancient Greek and Latin authors can be found in the very useful book of Murphy-O’Connor, St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology. It not only supplies a translation of the ancient texts, but summarizes the work of the archaeologists who have labored for over a century (since 1896) excavating the site of ancient Corinth (see Corinth: Results of Excavations Conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens [18 vols.; Princeton, 1929–1997]). Fundamental to the study of ancient Corinth are two works by Wiseman, “Corinth and Rome I: 228 b.c.–a.d. 267” and The Land of the Ancient Corinthians, on both of which Murphy-O’Connor heavily depends, as he himself admits. See also Furnish, “Corinth in Paul’s Time,” for good illustrations.

When one looks at a plan of Roman Corinth in Paul’s day (fig. 2), one studies it from the perspective of Acrocorinth, therefore looking toward the north. From the forum, which more or less corresponded to the agora of ancient Corinth, the Lechaeum Road (8) led to the northern city-wall. Near to the wall and to the west of the road were the Asclepieion and the Lerna Fountain. Access to that road from the forum was gained by a massive gate, called Propylaea (12). To the right of that gate was the Peirene Fountain (11). Leading north from the gate was a ramp to the Lechaeum Road, which was flanked on the left by the North Basilica (7) and on the right by the colonnaded Peribolos (Basilica) of Apollo (10). To the west of that basilica and perpendicular to its southern end ran the Northwest Stoa (6), to the north of which was the Archaic Temple (3), dedicated to Apollo [?]. Farther north and beyond the courtyard of that temple was the North Market (2). The western edge of the temple’s courtyard was flanked by a road that turned and led westward to the city-state of Sicyon. Across the road was a colonnaded courtyard in the center of which was the Temple C (of Hera Acraea?[5]), and on the western edge of the courtyard was situated the ancient Glauke Fountain (4). To the south of Temple C was the large colonnaded court of Temple E, the Temple of Octavia (19), the main entrance to which, flanked by shops, opened also onto the road to Sicyon.

In the forum proper, one found to the west a small Temple of Tyche (16), the Monument of Babbius (17), and Temple G (of Apollo?[20]) and Temple F of Aphrodite (21). Within the forum, almost due east of the Temple of Aphrodite, was a line of structures: a stone platform, the Bēma or judicial tribunal (26), shops (25), a structure dedicated (it seems) to Artemis of Ephesus, and more shops. To the east of these structures were the Julian Basilica (36) and the Tabularium or Records Office (35). The south border of the forum was marked by the South Stoa (27), onto which a number of structures opened. Chief among them was the City Council Chamber (29), and nearby a shrine to Sarapis (probably 28). To the south of it was the South Basilica (31). The forum itself was the most important part of Roman Corinth, and in the center of it was a great statue of Athena (14).

When leaving the forum of Roman Corinth to the south, just behind the South Basilica, one met the juncture of four roads: one led to the east and the Cenchrean Gate, which gave access to the road going to Corinth’s other port, Cenchreae; the second road headed toward the Southeast Gate and to Mycenae; the third road headed south, skirted the Acrocorinth on its west side, and led to Tenea; and the fourth road led southwest to the Phliasian Gate and the town of Phlius (figure 1).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alcock, S. E., Graecia Capta: The Landscapes of Roman Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Arafat, K. W., Pausanias’ Greece: Ancient Artists and Roman Rulers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) 90–97.

Broneer, O., “The Apostle Paul and the Isthmian Games,” BA 25 (1962) 2–31.

———, “Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis,” Hesperia 10 (1941) 388–90.

———, “Corinth: Center of St. Paul’s Missionary Work in Greece,” BA 14 (1951) 78–96.

———, Isthmia I: The Temple of Poseidon (Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1971); Isthmia II: Topography and Architecture (1973).

———, “The Isthmian Victory Crown,” AJA 66 (1962) 259–63.

———, “Paul and the Pagan Cults at Isthmia,” HTR 64 (1971) 169–87.

———, The South Stoa and Its Roman Successors (Corinth: Results of Excavations …, Vol. 1, part 4; Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1954) 100–155.

Callaway, J. A., “Corinth,” RevExp 57 (1960) 381–88.

Engels, D., Roman Corinth: An Alternative Model for the Classical City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

Feger, R., “Cicero und die Zerstörung Korinths,” Hermes 80 (1952) 436–56.

Finegan, J., “Corinth,” IDB, 1:682–84.

Freeman, S. E., The Excavation of a Roman Temple at Corinth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1941).

Furnish, V. P., “Corinth in Paul’s Time,” BARev 14/3 (1988) 14–27.

Gill, D. W. J., “Corinth: A Roman Colony in Achaea,” BZ 37 (1993) 259–64.

Jacobson, D. M., and M. P. Weitzman, “What Was Corinthian Bronze?” AJA 96 (1992) 237–47.

Larsen, J. A. O., “Roman Greece,” An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome (6 vols.; ed. T. Frank; Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1938), 4:259–498.

Lenschau, T., “Korinthos,” PWSup 4 (1924) 991–1036.

Meyer, E., “Korinthos,” Der kleine Pauly (5 vols.; ed. K. Ziegler and W. Sontheimer; Stuttgart: Druckenmüller, 1964–75); 3 (1969) 301–5.

Murphy-O’Connor, J., “Corinth,” ABD, 1. 1134–39.

———, “The Corinth That St. Paul Saw,” BA 47 (1984) 147–58.

———, “Corinthian Bronze,” RB 90 (1983) 80–93.

———, St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology (GNS 6; 3d ed.; Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002).

Oster, R. E., “Use, Misuse and Neglect of Archaeological Evidence in Some Modern Works on 1 Corinthians (1 Cor 7, 1–5; 8, 10; 11, 2–16; 12, 14–26),” ZNW 83 (1992) 52–73.

Robinson, H. S., “Excavations at Ancient Corinth, 1956–63,” Klio 46 (1965) 289–305.

Romano, D. G., “Post-146 B.C. Land Use in Corinth, and Planning of the Roman Colony of b.c.,” The Corinthia in the Roman Period (ed. T. E. Gregory; Ann Arbor: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1993) 9–30 and fig. 3.

Rothaus, R. M., Corinth: The First City of Greece: An Urban History of Late Antique Cult and Religion (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 139; Leiden: Brill, 2000).

Salmon, J. B., Wealthy Corinth: A History of the City to 338 BC (Oxford: Clarendon, 1984).

Scranton, R., et al., Kenchreai: Eastern Port of Corinth: I. Topography and Architecture (Leiden: Brill, 1978).

———, Monuments in the Lower Agora and North of the Archaic Temple (Corinth: Results of Excavations …, Vol. 1, part 3; Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1951).

Waele, F. J. de, Corinthe et Saint Paul: Les antiquités de la Grèce (Les Hauts Lieux de l’histoire 15; Paris: Guillot, 1961).

———, “Korinthos,” PWSup 6 (1935) 182–99.

———, “The Roman Market North of the Temple at Corinth,” AJA 34 (1930) 432–54.

Walbank, M. E. H., “The Foundation and Planning of Early Roman Corinth,” JRA 10 (1997) 95–130.

———, “What’s in a Name? Corinth under the Flavians,” ZPE 139 (2002) 251–64.

Weinberg, S. S., The Southeast Building, the Twin Basilicas, the Mosaic House (Corinth: Results of Excavations …, Vol. 1, part 5; Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1960).

Williams, C. K., II, “Corinth 1977, Forum Southwest,” Hesperia 47 (1978) 1–39.

———, “The Refounding of Corinth: Some Roman Religious Attitudes,” Roman Architecture in the Greek World (ed. S. Macready and F. H. Thompson; London: Society of Antiquaries, 1987) 26–37.

———, and J. E. Fisher, “Corinth, 1970: Forum Area,” Hesperia 40 (1971) 1–51.

Willis, W., “Corinthusne deletus est?” BZ 35 (1991) 233–41.

Wiseman, J., “Corinth and Rome I: 228 B.C.–A.D. 267,” ANRW II/7.1 (1979) 438–548.

———, The Land of the Ancient Corinthians (Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 50; Göteborg: Åström, 1978).

AB The Anchor Bible

BA Biblical Archaeologist

BA Biblical Archaeologist

AJA American Journal of Archaeology

HTR Harvard Theological Review

RevExp Review and Expositor

IDB G. A. Buttrick (ed.), The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (4 vols.; Nashville: Abingdon, 1962)

BARev Biblical Archaeology Review

BZ Biblische Zeitschrift

AJA American Journal of Archaeology

PWSup Supplement to PW

ABD Freedman, D. N. (ed.), Anchor Bible Dictionary (6 vols.; New York: Doubleday, 1992)

BA Biblical Archaeologist

RB Revue biblique

GNS Good News Studies

ZNW Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche

PWSup Supplement to PW

AJA American Journal of Archaeology

JRA Journal of Roman Archaeology

ZPE Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

BZ Biblische Zeitschrift

ANRW H. Temporini and W. Haase (eds.), Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1972–)

Fitzmyer, J. A. (2008). First Corinthians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Vol. 32, pp. 21–29). New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Oops, this is members-only content

This page requires at least a Basic level membership to access the teaching.

Audio

Oops, you don't have access to this content

Categories

2 thoughts on “Intro to the Book of Corinthians: Foundation of the city of Corinth”

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Wow! I learned so much and making all kinds of connections with the new testament – first century writings. I love how things fit together and align with Torah and the character and honor of our King!

Context, context, context!!!!! Ah, how much more we need to learn if we truly want to understand Him and His ways – versus how we’ve been taught or brought up. Shed the old stuff and come into the honorable relationship with our King through His Son, our Master, Yeshua.

Todah rabah Rico!!

Rico,

Loved this teachings!! Todah Rabah for all your efforts and time to put this teaching together for us!!

“The Truth will set you free”!!

Blessings!! Pray you are healing from your surgery!!

Sinda